ChatGPT to reignite the love of learning

The rise of ChatGPT has prompted debate in academic circles as to whether artificial intelligence (AI) should be banned for students (and professors). Some universities have proudly banned ChatGPT while others are harnessing its benefits. For example, Princeton, Yale and Syracuse Universities have viewed AI as a potentially useful tool, not a threat and developed policy with guidance to academic staff on how to incorporate AI into course syllabus. One major concern is the potential for abuse, such as students turning in AI-generated essays or programming codes as one’s own work.

The fear is that using AI would reduce the quality of learning. Having short cuts to quick wins would make students lazy. And university administrators would be blamed for failing for suppress academic misconduct. There are concerns too about AI cannibalizing the work of academics. A wealthy retiree, a former entrepreneur whom I know for many years, once asked me: “will you guys [professors] be replaced by AI?”

But one argument is missing here. Academic cheating is a multibillion-dollar industry. If you have not heard of it, a platform called Chegg offers students, at a small fee, with all the help to get high grades. A simple Google search will yield similar platforms and services. Students have confessed to using education platforms such as Chegg and many others, which offer help with homework and textbook answers, to cheat. There are also countless ghostwriting, contract cheating and other services available. Not to mention the “dark web” that can do almost anything for students.

Academic cheating is a multi-billion dollar industry. Banning AI is hardly going to help when there are thousands of ways to cheat.

Academia is all too optimistic about anti-plagiarism software and academic integrity policies catching all the bad apples. Banning AI is hardly going to help when there are thousands of ways to cheat.

And it seems ChatGPT is likely to only get a student a C grade anyway, according to informal experiments by American university professors in putting the bot through tests. The tentative conclusion is that ChatGPT is not a great cheating tool because it requires some skill to get it to produce targeted, high-quality results, and even so, the output can include errors. One needs to know “prompt engineering” — a new yet still undocumented sets of skill used to interact with AI to harness its best potential.

AI is not a great cheating tool because it requires prompt engineering skills, a new sets of skills that are rapidly emerging, in response to the rise of large-language models (LLM) AI.

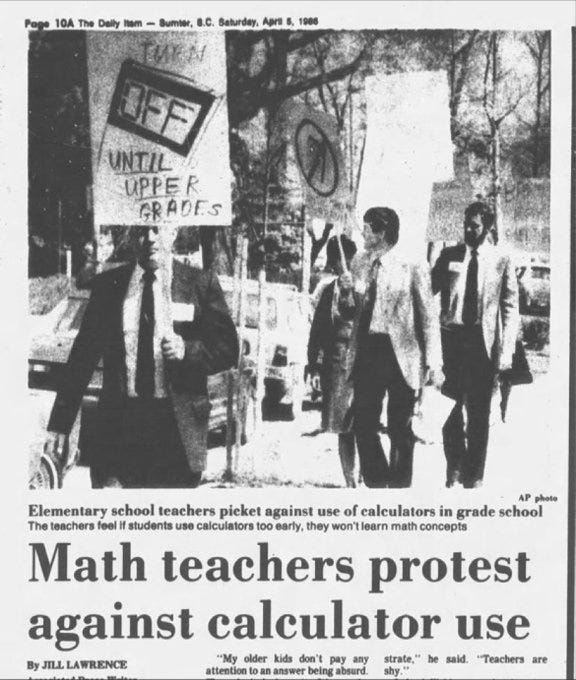

The resistance toward ChatGPT in academia is reminiscent of maths teachers’ protest against the use of calculators in Washington in April 1988. This was when powerful pocket size calculators emerged in the 80s. But calculators did not remove the need to learn algebra and calculus.

Nor did Microsoft Excel remove the need to learn about matrices and computational skills. Instead, these tools automated low-level, repetitive tasks, allowing us to get into higher-level, more complex thinking, and to be more creative.

With calculators, maths teachers have taught algebra differently. For example, instead of teaching rigid steps in how percentages and fractions are calculated, students can be asked to explore alternative ways to arrive at an answer, using calculators. The focus shifts away from rote memorization toward discovery in learning. As a teaching tool, AI including ChatGPT can perhaps be seen in a similar light.

Resistance to AI reminds of us the protest against calculators in the 1980s. Academics can be a creative (lead) user of AI, by adapting what works in their own fields.

ChatGPT and AI in general require academia to change their perspectives in three areas: how they view their role in learning, and how they design pedagogy and assessments.

Responsible use of AI policy

First, academia can lead in providing the wisdom and awareness with which to judge and interact with output from AI. Knowledge co-production with AI can become what academia focuses on. A crucial first step is to devise a responsible AI use policy which can include having students acknowledge AI use in their assessed work.

Creating examples

Second, curriculum design has to change with the advent of AI. In any given topic, AI can create plenty of examples in seconds – from coding a simple website in HTML, regression equations in Python or R, to drafting a CEO’s speech in a crisis. Students can critically evaluate these examples as part of learning.

Grammaring

AI can help learning by correcting grammar, suggesting the appropriate semantics (“do I say drink or take the medicine?”), analogy, metaphor or even the words more culturally relevant in one country than another. Think of how that will help a second or third language speakers learn language or those from the Global South who might have restricted access to quality education materials.

Versioning

AI can also quickly offer different versions of the same thing, which can help in learning how to, say, write for different target audiences, and to write with greater clarity.

Debating-Augmenting

Asking AI questions can also help in developing debate and argument, especially when the AI is asked to refute one’s ideas, which learners can follow up on with rebuttals. For example, learner can debate: is sugar tax effective to prevent health crisis? Is climate change real? — using this approach.

Role playing

AI can also help in role playing. For example, learners can ask the AI to write a fundraising statement for a social enterprise, first as Mother Teresa, then as Albert Einstein, to try and better understand the historical figures.

Weeding out plagiarism

To weed out plagiarizing, we can learn to spot the structure and style typically churned out by an AI. Students can create prompts in ChatGPT to produce results, then learn by observing its common patterns and stylistics, and then be critical about the results. This can enhance more authenticity in thinking and writing.

Assessments: from chatbots to visual recognition

Third, AI will require a change in academic assessments. We can build customized AI chatbot as a repository of knowledge to complement lectures, readings, cases, tutorials — in a single interface. We can then sit learners down for sessions with customized AI chatbots. After a session, the chatbots can recommend personalized learning instructions to plug the gaps detected.

Visual-recognition AI can also help to grade maths equations, sketches of an idea or a prototype. It can compare and contrast work from different student cohorts to assess their strengths and limitations, and offer support. It can also catch salient key words in essays, etc. Different pedagogical techniques can be assessed by AI in terms of efficacy and speed.

The inevitability of AI in academia

If AI is an elephant, then academia are the six blind men, each touching a different part of the massive entity. As AI penetrates email systems (e.g., in sentence completion or correction) and software (e.g., Microsoft Office apps, integration of AI into Bing, Google, Baidu search engines), it will be harder to evade.

AI will become another calculator or Google in our lives. ChatGPT it, Bing it, Ernie it, Midjourney it – these phrases will enter our daily lexicon. If surgeons can use AI to detect cancer with greater precision and speed while maintaining the final call, there seems to be little risk for academia to embrace AI as a new avenue for knowledge discovery, creation and dissemination. The age of human-machine symbiosis is arriving.

The original version of this article was published in SCMP online on 22/03/2023.